1910 – 1924

James Connolly was badly wounded and brought to Dublin Castle. Patrick Pearse was brought to Arbour Hill, before transferring to where the rest of the leaders were located, in Richmond Barracks. There they were court-martialled and sentenced to death. They were transferred to Kilmainham Gaol. Here, they were visited by loved ones, and wrote their final goodbyes. It was also here that another leader, Joseph Plunkett, married Grace Gifford in the Gaol chapel the night before he was shot. Between the 3rd and 12th of May 1916, fourteen men were executed by firing squad in the Stonebreakers’ Yard of Kilmainham Gaol. Seven of them had been the signatories of the Proclamation. These were Thomas Clarke, Seán Mac Diarmada, Thomas MacDonagh, Patrick Pearse, Éamonn Ceannt, James Connolly, and Joseph Plunkett.

A party there will put the bodies close along side one another in the grave (now being dug), cover them thickly with quicklime (ordered) and commence filling in the grave. One of the officers with this party is to keep a note of the position of each body in the grave, taking the name from the label. A Priest will attend for the funeral Service.

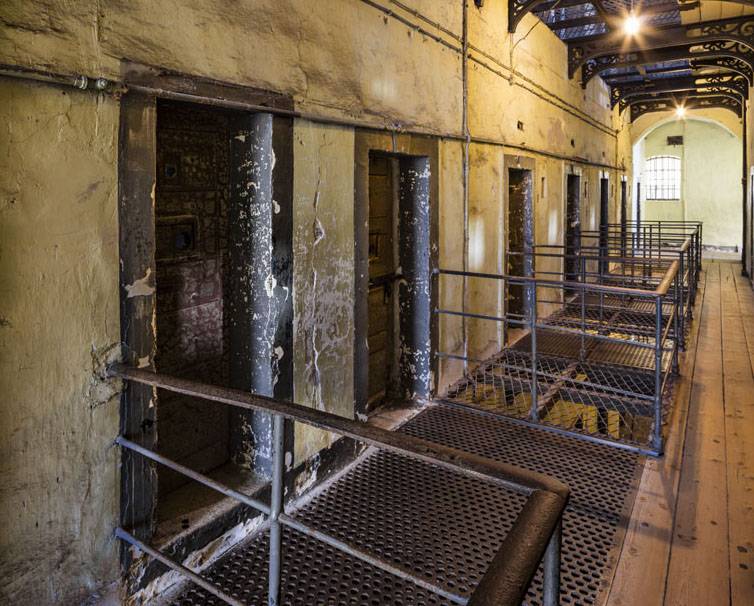

The War of Independence was fought between the Irish Republican Army and British forces. These last included the two infamously violent special units known as the Auxiliaries and the Black and Tans. Kilmainham Gaol, which had been closed since the executions of 1916, was now reopened as a military detention centre, once more to receive Republican prisoners. Harsh security was enforced there until the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921, when truce negotiations achieved an amnesty.

The signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, with its concession of the six counties in Northern Ireland and its retention of the Oath of Allegiance, led directly to the Irish Civil War which broke out in June 1922. Pro- and anti-Treaty groups now organised against each other. Fighting to maintain the Treaty were the National (Free State) Army, with support from the British. Protesting against the Treaty were the Irish Republican Army, Cumann na mBan, and Na Fianna Éireann (a nationalist youth organisation).

The new Free State Army now took control of Kilmainham Gaol, and employed it for the same purpose it had been used for during the previous decade; to detain and sentence Republican political prisoners. This was demanding and painful duty for those required to act as guards, for many of their prisoners had recently been their comrades. Both men and women were held in the Gaol, including leading figures such as Maud Gonne McBride, Nora Connolly, and Eamon de Valera. The Republicans surrendered in May 1923, and prisoners began to be transferred from the now dilapidated, damp, and dark Gaol. De Valera was one of the last to leave in 1924, after which the Gaol was allowed to fall into abandonment. The official Closing Order was issued by the Minister for Justice of the Irish Free State in 1929.