Restoration

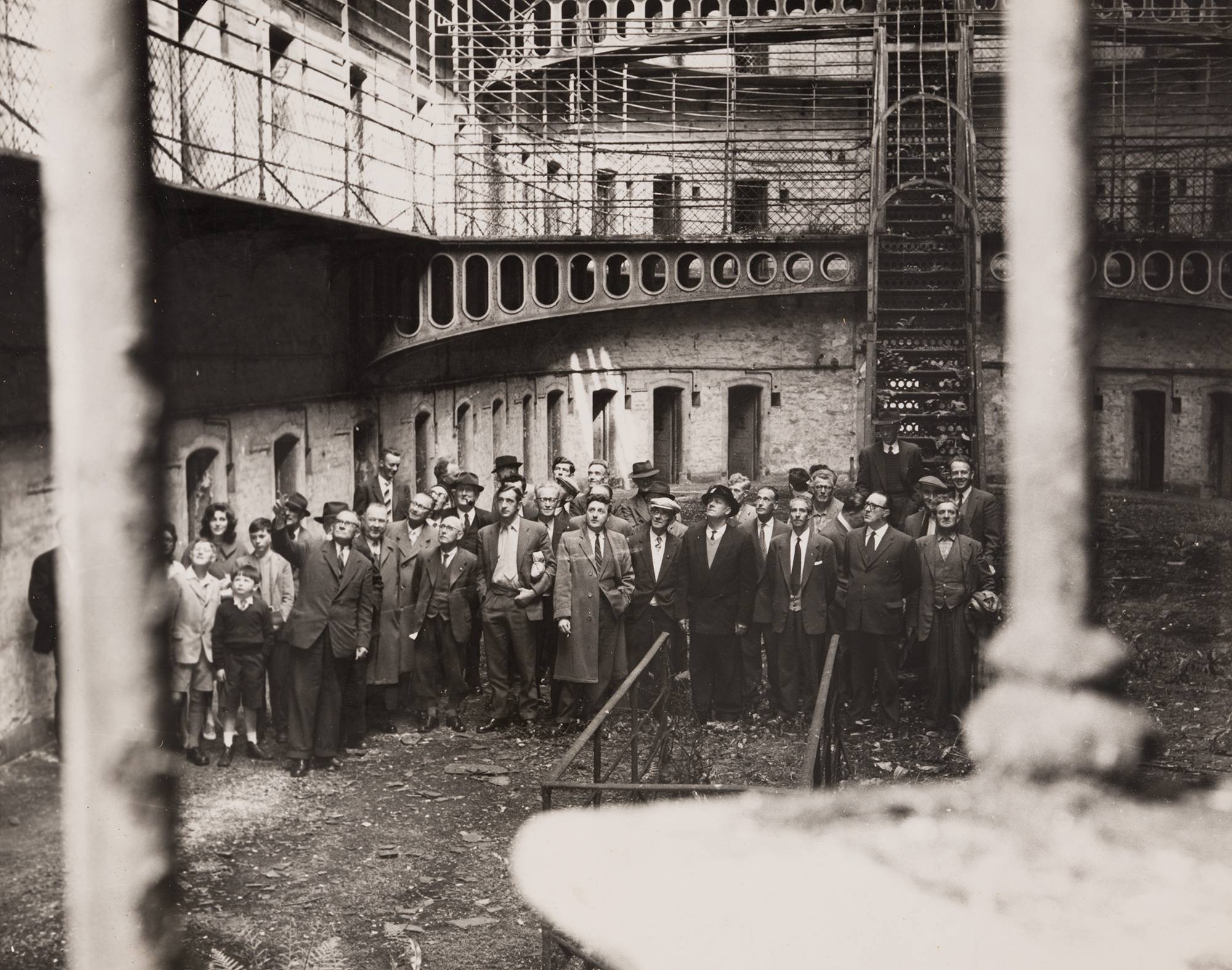

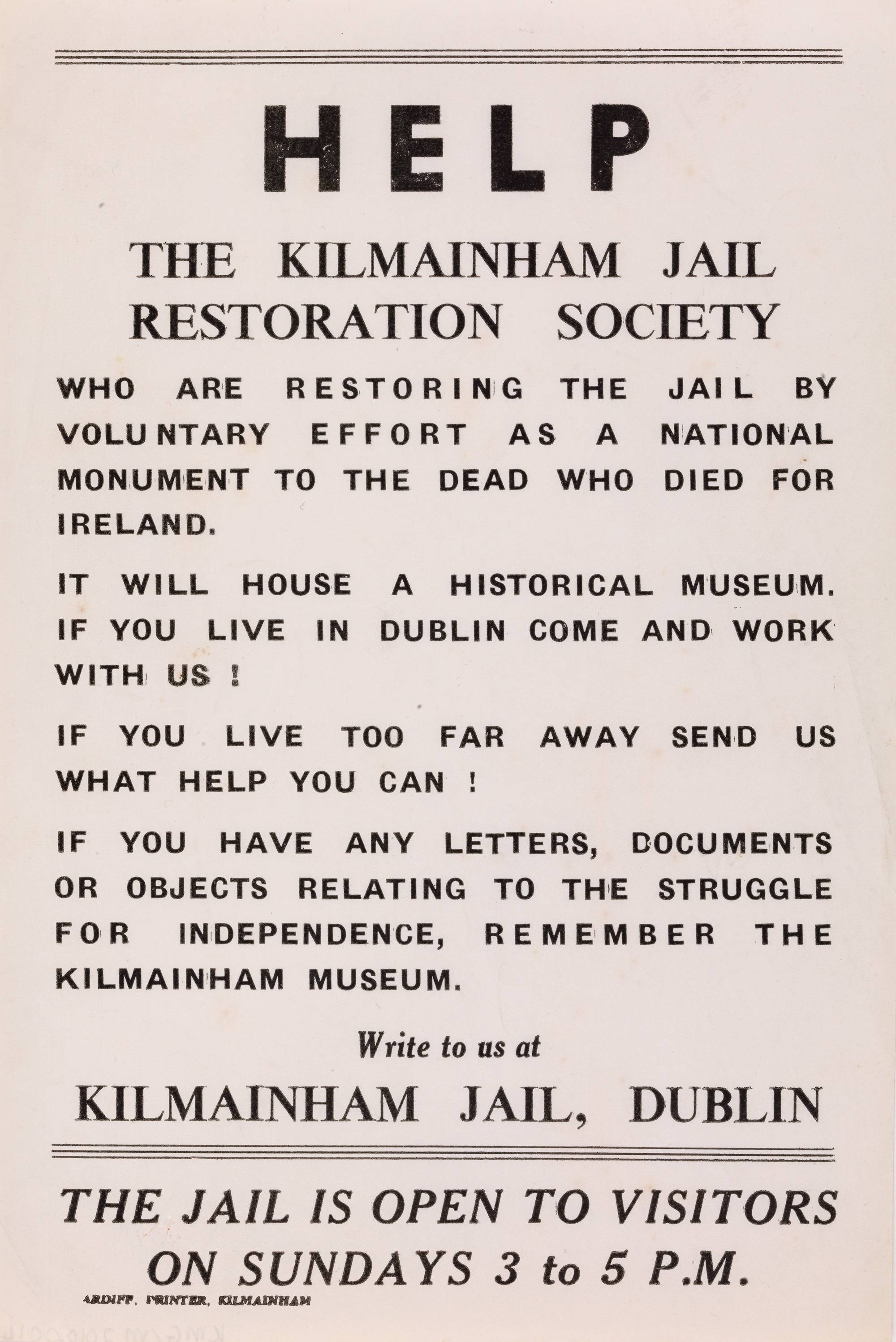

The work of the Kilmainham Jail Restoration Society did not stop in 1966 however. They spent the next twenty years carrying out an extraordinary amount of voluntary repair work on the building. This included the removal of trees and shrubs which had taken root, the removal of pests, the replacement of broken glass, the removal of rusted ironwork, and the replacement of rotten wood and plaster. Funds to support these efforts came from public donation, government funding, and enterprising ventures involving the Gaol space, such as leasing it as film set. Movies such as The Quare Fellow (1962), The Italian Job (1969), and The Last Remake of Beau Geste (1977) were all partially filmed at the Gaol. They also received huge popular support from tradesmen, having as many as 200 working pro bono on the site at evenings and weekends during the 1960s.

… Much to the dismay of the pigeons overhead and rats underfoot we set out to first push back the advance of nature and arrest the ravages of time and neglect.