Prison Life

Overcrowding was caused by the use of the Gaol as a holding depot for convicts sentenced to transportation to Australia, by the onset of the Great Famine (and the massive increase in offences relating to the theft of food), and by the incarceration of those with mental illnesses as criminals. Insufficient accommodation meant that for this long period, cells which had been designed for one person, at one point held as many as five at a time. The Vagrancy (Ireland) Act of 1847, which compelled the arrest of beggars, worsened conditions further.

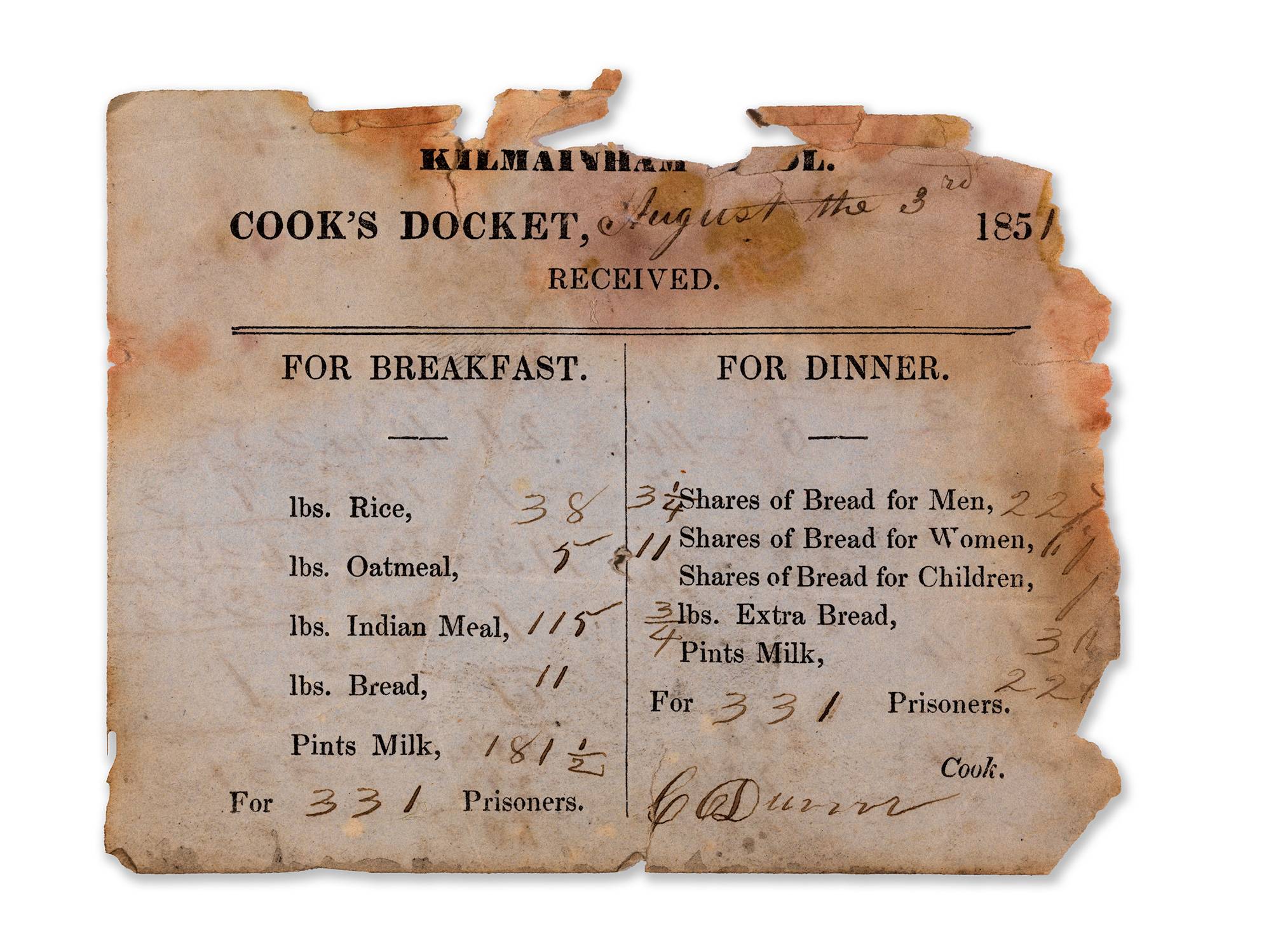

Prisoners also worked within the Gaol. A sentence of hard labour for a man consisted of manually breaking stones in the Stonebreakers’ Yard, and for women meant working in the laundry. After 1844, inmates also made and repaired their own prison uniforms. Other work involved cleaning the cells and common areas, providing care (of a sort) to the ‘lunatics’. Children whose sentences were longer than two weeks received weekly school lessons from the chaplain.

Throughout the history of the Gaol, the vast majority of its population were ordinary criminals rather than political prisoners. When the Gaol first opened, half of all prisoners were debtors. The other crimes were divided between robbery, assault, rape, murder, bigamy, illicit distilling, and counterfeiting coins. Those who were found to be mentally disabled were also jailed, as were beggars. Food-related theft rose dramatically during the famine years. The offences involved in most cases were very minor; the debt owed by so many early convicts generally consisted of a tiny amount of money.

Conditions for women remained persistently worse than those for men. If a woman was the mother of a baby under twelve months old, the baby often came with her and stayed for the duration of her sentence. After the bright and airy new East Wing was built in 1861, men were transferred there, while women remained in the darker, older West Wing. Conditions were also different depending on the status of the prisoner. While poorer inmates were fully subject to the Gaol system, rich and prominent prisoners such as Charles Stewart Parnell could comfortably furnish a number of cells with their own possessions, and interact freely with visitors.

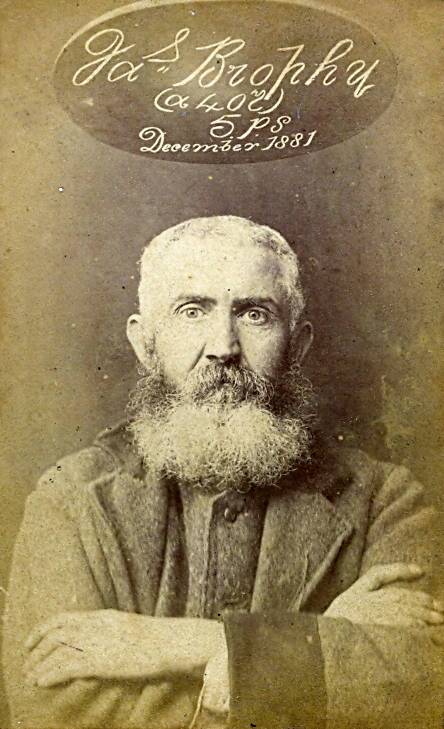

The details of those who were incarcerated in Kilmainham Gaol are contained in twenty-four large volumes. These are now located in the National Archives of Ireland.